The Shock of Learning My Last Name Is a Slave Name (P1)

The Shock of Learning My Last Name Is a Slave Name

I’m dropping this on the last day of Black History Month—not because I planned to, but because this revelation knocked the wind out of me, and I’m still processing it.

For my entire life, my last name was just that—my last name.

A signature on documents. A name I introduced myself with. Nothing more, nothing less.

Until I found out the truth.

My Last Name Is a Slave Name.

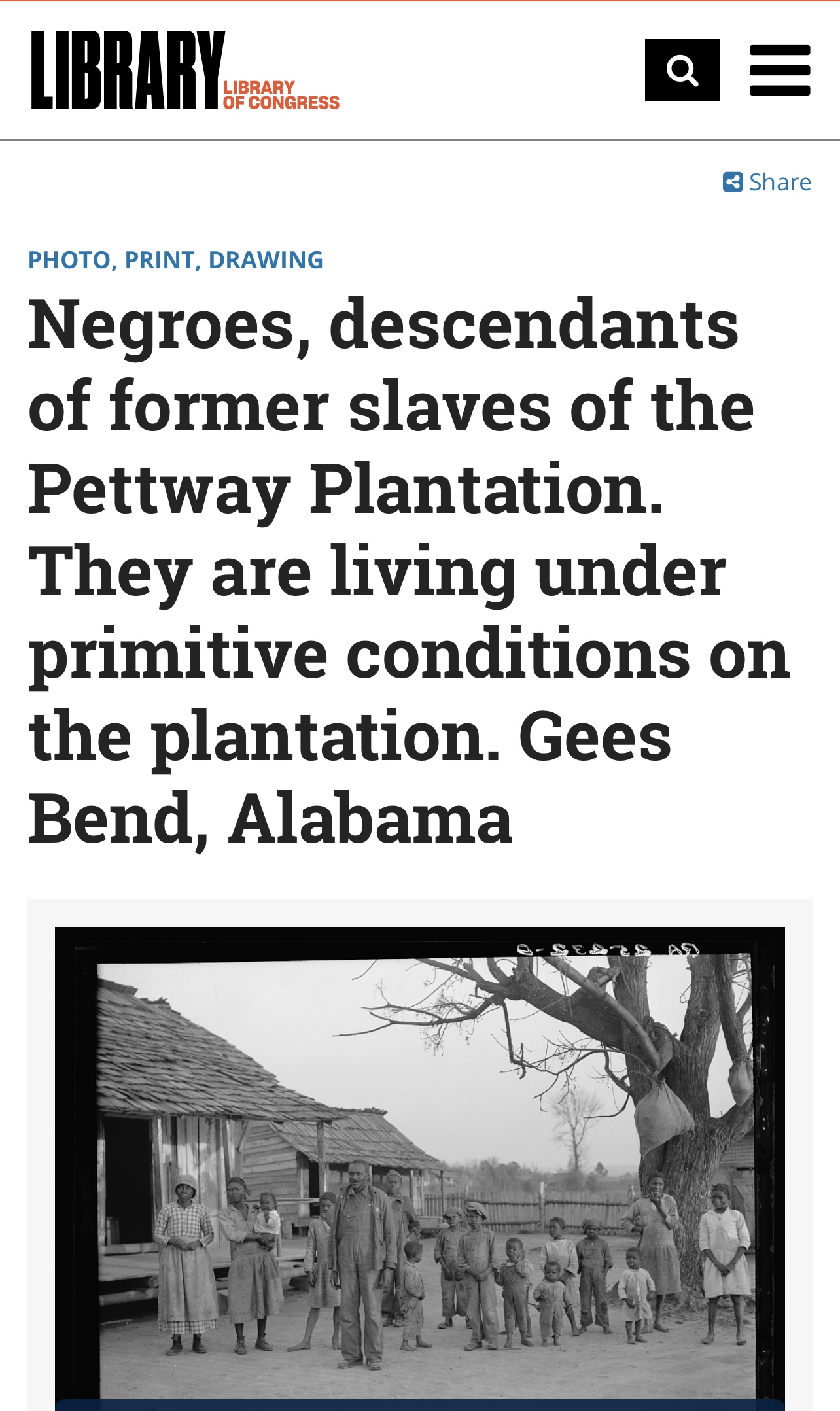

Confirmed. Straight from the Library of Congress. And let me tell you, it’s still sinking in.

The name I carry isn’t just a name—it’s a receipt of oppression. A reminder that my ancestors were stripped of their identity and forced to take the name of the plantation that enslaved them.

I wasn’t ready for that.

I always knew Black history was full of pain and resilience—including the legacy of slave names. But when history knocks on your front door and calls you by name, it hits differently.

Less than two weeks ago, I typed “Pettway Plantation” into Google.

What I found? Poked the bear in me.

I couldn’t just move on. You know me—I don’t do surface-level. I went deep.

And what I found? Whew.

The Origin of Gee’s Bend and the Pettway Name

To understand the weight of my name, I had to go all the way back to 1816—to a man named Joseph Gee.

Gee, a North Carolina enslaver, acquired 6,000 acres of land along a horseshoe bend in the Alabama River. He built a plantation with 17 enslaved people—and that land much later, became Gee’s Bend.

Fast forward to 1845—mounting debts forced the Gee family to sell the plantation, including 98 enslaved people, to Mark H. Pettway— enslaver, and the sheriff of Halifax County, North Carolina.

The following year, Pettway packed his family into wagons and moved to Gee’s Bend.

His 100 newly enslaved men, women, and children? They walked.

From North Carolina. To Alabama. On foot.

And while Gee left his name on the land, Pettway left his name on the people.

Stripped of Identity, Trapped by Economics

On plantations throughout the South, enslaved people were forced to assume the names of their owners—erasing their original identities, histories, and family connections.

As Hargrove Kennedy, a Gee’s Bend descendant, once put it:

“What his name was when he came here [from North Carolina], I don’t know. A heap of people think that all these folks here was Pettways, but that ain’t what they started with. They ain’t even no kin, hardly.”

After emancipation, my ancestors were legally free but economically trapped.

Many stayed on the land, locked into tenant farming and sharecropping, working fields they would never own. Unfair contracts, dishonest landlords, and unpredictable harvests made sure they stayed in debt—a system designed to keep them stuck.

The Pettway plantation changed hands after the Civil War, but the cycle of exploitation and poverty remained—locking generations of Black families, into a fight to survive. What I love is the Pettway family thrived throughout the generations (more on that in part 2)

Processing the Weight of My Name

Finding out that my last name carries the weight of slavery hit me like a gut punch.

This wasn’t a name passed down through love and legacy. It was forced. It was ownership. It was survival.

And yet, despite everything, my family endured.

They built lives.

They held onto each other.

They refused to be erased.

That kind of strength, resilience, and fire?

That’s in my DNA.

And I have more to uncover.

Because in Part 2, I drop another huge bomb—one that ties my family name to a moment in history that changed everything.

Marquesa

In Person, Virtual, the Connection can be

t+ The Best, Hottest, Results-Driven, Technology resources delivered to your inbox.

We hate SPAM. We will never sell your information, for any reason.